How COVID-19 Facilitated Person-centered HIV Care in Zambia

May 4th, 2021 | viewpoint

When the COVID-19 lockdown hit Zambia in March 2020, HIV programs had to suddenly and drastically reduce health facility visits, while also accelerating efforts to provide people living with HIV with antiretroviral (ARV) medications so they could remain virally suppressed. These actions kept people living with HIV safe during the pandemic and strengthened person-centered care by—

In major HIV clinics in Zambia in 2018, JSI’s Michael Chanda estimates that providers supported through the USAID SAFE Project saw an estimated 250–300 people in a given morning. By 2019, with the ongoing push to get clients onto multi-month refills, that number had dropped to 30–50. Then COVID hit. Now providers see 5–10 people in a morning, all of whom have serious issues that require medical follow-up.

“The numbers have reduced, which has increased efficiency,” Dr. Chanda explains. “The few who come, we can now spend more time, we can respond to their questions more appropriately. Those who require things like resistance testing, we are missing very few of them now because we are able to follow the protocols much more closely.”

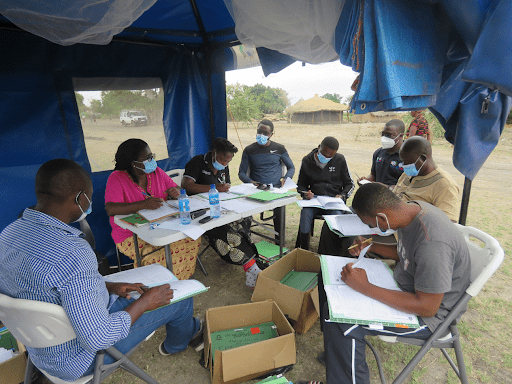

The vast majority of clients, stable and virally suppressed, get six months of ARV drugs at a community pick-up point or a smaller clinic near their work or home. Clinics have become more efficient, making client appointments not just by date but also with an appointed time. Differentiated service delivery has, at long last, become the norm for hundreds of thousands of people living with HIV.

Differentiated service delivery is a complicated term for a simple concept: design health care (medications, refills, and labs) around the daily routines and needs of clients. For years this was an uphill battle. Providers feared that patients wouldn’t take medicines properly if they got six months’ worth at once. Clinics didn’t have enough room to store so many boxes of pills. Labs needed patients to come in for blood draws.

If ever there was a time when differentiated service delivery models were prompted in Zambia, it is now.”

“Initially,” Dr. Chanda recalls, “there was a good proportion of pharmacists who just put their foot down. They just never trusted that we could give drugs for six months to people.” Providers were concerned about pharmacovigilance, that patients might not safeguard or take medications correctly. Even patients themselves sometimes presented a barrier. “Our clientele is such that they like coming to the facility. There is a category of our clients that believe that unless they come to the facility to see the doctor, to see the clinician, to tell the clinician what their problem was, they were not going to be treated.”

And then COVID hit. Overnight, years of incremental policy and implementation changes were quickly and fully translated into reality. Large-scale HIV programs had to up-end years of messaging and routine care, instructing tens of thousands of clients not to come to the health facility unless it was a life-threatening situation. It was an unsetting time for everyone.

“With the onslaught of COVID, the fear was that our [number of patients on treatment] would go down,” said Dr. Chanda, explaining how his team on the USAID SAFE Project moved quickly to retain clients by equipping community health volunteers with phones. “We made sure that, since contact between people was reduced to a minimum, to only when necessary, we continued phoning people from time to time.” But instead of merely calling patients with appointment reminders, as in the past, volunteers were providing continuous adherence counseling by phone to a cohort of carefully selected clients.

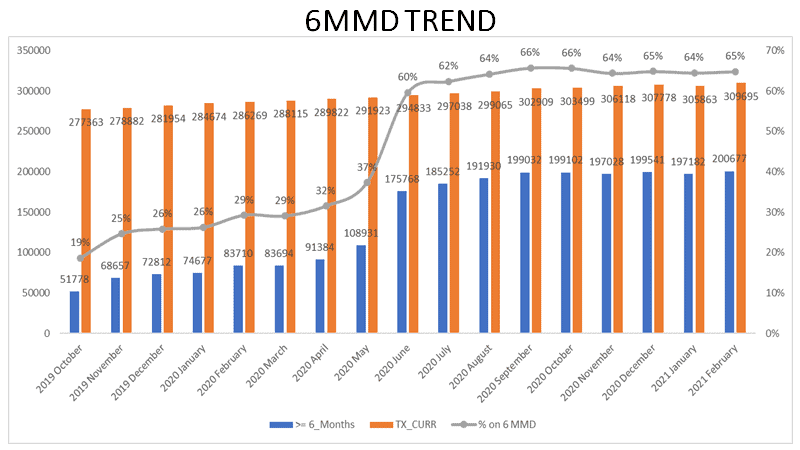

Collectively, these community-based adherence strategies have achieved their intended result: from March to June 2020, the proportion of clients on six months of multi-month dispensing (6MMD) doubled.

Dr. Chanda is quick to add that these changes have not compromised the quality of HIV care. SAFE currently supports over 300,000 patients on ARV therapy, and by March 2021, of the more than 80% of eligible clients who had their viral load tested, 94% were virally suppressed. Many clients now get their medications at community collection points. On a designated day, a client can collect her ARVs and have blood taken for viral load monitoring.

Community-based volunteers have also evolved to support the new model. Pre-COVID, volunteers predominantly called patients to come back to the facility for viral load tests or clinical exams. “We have now perfected the art and science of [differentiated service delivery] models,” declares Dr. Chanda.

Much of what we did in the facility, we have discovered, we can actually do with the clients in the comfort of their home.”

In this year of loss and isolation, it is gratifying to know there have been some extraordinary public health gains. “Now,” reflects Dr. Chanda, “things are completely different. A lot of what we used to do in the clinic can now be done virtually and this is another practice that we have inculcated into community-based volunteers, clinicians, and our nurses. And it will continue going forward.”

We strive to build lasting relationships to produce better health outcomes for all.