Five Reflections from the Right Here, Right Now Global Climate Summit 2022

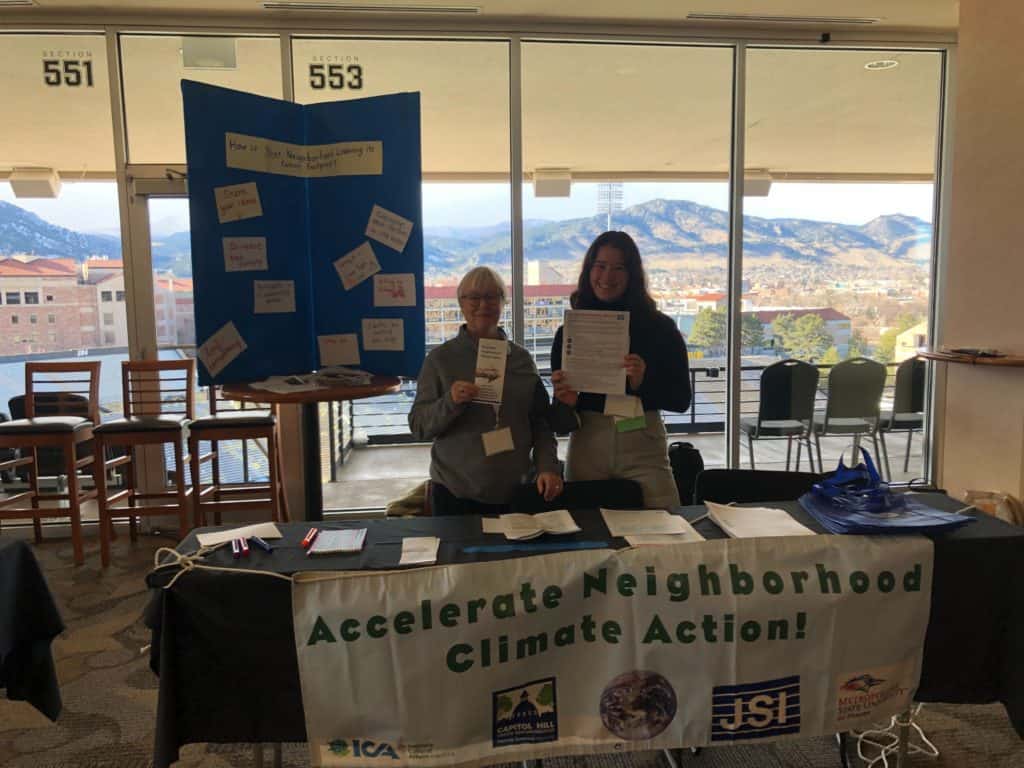

United Nations Human Rights and the University of Colorado Boulder co-hosted the Right Here, Right Now Global Climate Summit December 1–4, 2022. The JSI Colorado office and partner Accelerate Neighborhood Climate Action exhibited our collective efforts to mobilize Denver neighborhoods for climate action planning. Five reflections arose from connecting with other exhibitors working on climate crisis action, hearing from experts, communities, and advocates, and learning with over 4,000 attendees.

- Climate change and human rights are inextricably intertwined. Climate change affects widely recognized human rights, including to life, culture, self-determination, development, food, water and sanitation, housing, and a healthy environment. Solutions to the crisis require scientific, political, educational, cultural, and industry interventions and innovations, as well as a deep recognition of the expertise and value of traditional knowledge and wisdom.

- The climate crisis is a symptom of larger systems of oppression. At the opening panel session “Understanding Climate Change as a Matter of Human Rights,” panelist Kera Sherwood O’Regan (Kāi Tahu), an indigenous and disabled climate justice expert and community advocate from Te Waipounamu, New Zealand, used the metaphor of a three-legged stool for climate change. Its negative effects as the stool top, and its legs the systems of oppression and exploitation of people and the land—colonialism, capitalism, and ableism—that have caused the climate crisis. If we don’t address both the consequences of the crisis and its root causes, these systems will continue to perpetuate inequities, including health disparities.

- Our fates due to climate change are interconnected. The consequences of climate change are manifesting everywhere, from the summit’s host community of Boulder, through which the Colorado River flows is the driest it has been in 1,200 years, to the homes of the presenters, where the urupā (burial grounds) of Māori cultural heritage sites in New Zealand falling into rising seas.

- “There are no vulnerable populations, only populations put in vulnerable situations. Vulnerability is not a natural occurrence,” said summit panelist Astrid Puentes Riaño, a lawyer with more than 20 years of experience in environmental law, human rights, and climate change in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. While our fates due to climate change are interconnected, they are also inequitable. The communities that suffer the worst effects are least responsible for climate change, and the stakes are not the same. After noting that 82 percent of crops were lost in Honduras in 2018, causing caravans of people to move north, Riaño noted that, “It is not the same to be a wealthy man or woman here in Boulder impacted by climate change as it is for a 14-year-old Indigenous girl migrating all the way from Central America. If she is lucky, she will get to the U.S. alive.”

- Most-affected communities understand the climate crisis best and have the wisdom, experience, and insights for solutions. We need diverse people guiding decisions on climate action because we need different solutions; the status quo is not working. As Kenyan social development specialist and climate and gender justice advocate Edna Kaptoyo said during a summit panel, “if we are not visible, our needs are not being met.” Communities that are experiencing climate injustice have systematically been excluded from conversations and decision-making, and we must find new ways of working together toward solutions. Traditional knowledge includes natural resource management solutions and adaptation techniques. Summit keynote Sheila Watt-Cloutier, global advocate for Indigenous rights and health, climate justice, and human rights gave examples about Inuit peoples’ innovations in building snow globes for warmth.

Climate action can be overwhelming; it requires imagining new solutions, challenging the status quo, and multi-level and -sector interventions. Yet, there is progress, from mutual aid efforts among neighbors focused on preventing hunger amidst crop destruction, to the establishment of the loss and damage fund (due in large part to the advocacy of a record 300 representatives from Indigenous communities at COP27). By working collectively and restoring relationships with each other and the land, a more livable and healthy world is possible.