COVID-19 Response Opens Doors to Overcoming Health Disparities

October 14th, 2021 | viewpoint

As COVID-19 swept across the United States, public health officials scrambled to reduce its damage by identifying and isolating people who had tested positive for the disease. The plan was for simple phone calls to inform people of positive tests and tell them to stay home and away from others.

But often those calls were anything but simple. There were language barriers. There was distrust. There were people who didn’t believe that COVID-19 was a threat. Many people were living paycheck-to-paycheck and couldn’t afford to take time off work. People often who had no other way to get food, diapers, or other necessities, even if they wanted to cooperate.

The callers found themselves embroiled in the fact that public health is about much more than health. Instead, to succeed, public health must address a complex intersection of health concerns, cultural and religious beliefs, the demands of daily living, economic constraints, and other complicating factors, even during a pandemic whose severity, for some, meant health should be the first—if not the only—concern. For JSI staff, this was familiar territory.

We could have never imagined something as vast as this,” says Julie Attys, JSI consultant. “We’re still responding to this. These are people who were probably struggling before COVID, but the pandemic made it worse. We realized we needed people from within communities to fill the gap with connecting people to care. That had to be embedded in our contact operations.”

JSI staff were part of the COVID-19 response from the beginning, first taking roles that grew out of initiatives in which they were already involved. As demands emerged and evolved, they moved into new roles, including staffing call centers; providing education and public health recommendations; developing communication campaigns; training, staffing, and supporting the expansion of telehealth; and bolstering vaccine rollout.

Throughout the various programs and initiatives, we ran into challenges and inherent weaknesses we’ve seen before. Community disinterest. Poor coordination. Communication breakdowns. Misaligned financial incentives.

Although this was on a larger scale, the solutions were the same. Across the initiatives and programs, we applied and amplified the lessons we’ve learned from previous efforts.

Collectively, staff, agencies, community organizations, and others involved in the pandemic response developed solutions to build bridges across communities and close the gaps that kept people from getting the care they needed. Although these solutions grew out of a crisis, they can provide a foundation for ongoing efforts to strengthen the public health system, reduce disparities, and increase equity.

The pandemic revealed holes in the public health system—people, and even communities, that fell through the cracks—like nothing before because it was so much bigger and has lasted so much longer than anything similar in the last century. It has acted as a giant lens, magnifying clearly what’s been going on for decades, according to Amy Cullum, senior consultant, emergency preparedness, U.S.

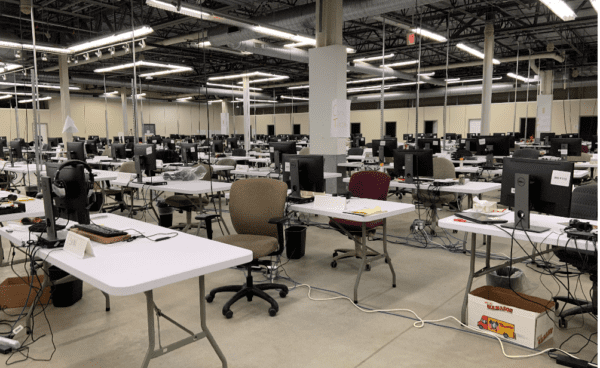

Cullum watched much of the pandemic unfold, spending much of her time at New Hampshire’s cavernous command center. JSI staff worked shoulder-to-six-feet-apart-shoulder with state officials and emergency responders to design case investigation operations and guidance, and, eventually, plan vaccination efforts for people who are homebound. Though they were in the same room, they met on Zoom to maintain social distance as they pieced together what was happening and reworked strategies to meet the ever-changing demands of the pandemic.

To a large extent, the public health and health care community was prepared. Public agencies and private sector partners routinely conduct planning exercises. JSI staff, with officials in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, had worked through emergency scenarios to identify and close gaps.

“We couldn’t have imagined something this big,” Cullum says. “Even though we had developed flu scenarios, we couldn’t really appreciate the impact this would have. Or the repeated trauma. Or how much of a sustained effort it would take.”

Through the months, the work morphed and grew as the disease spread and more was learned. Contact tracing continued and social services were looped in. Mask advisories gave way to mandates, along with a need for comprehensive messaging to encourage compliance. Health care overcame long-standing barriers to embrace telemedicine. Vaccines finally became available, and distribution channels opened.

We were pushed to overcome hurdles, there was no time to get derailed,” Cullum says. “And what came out of it were these amazing, innovative solutions and cohesive partnerships. People were open to doing things differently because that’s what was needed.”

As the world faces new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and adapts to revised safety protocols, public health concerns and priorities that had been overwhelmed by the urgency of the pandemic response are attracting attention again. The question now is, will things go back to how they were? Will the lessons and solutions developed during the pandemic be forgotten? Or will they be embraced and applied to improve non-pandemic health, to serve underserved communities, fill holes identified in the health care system, and further reduce disparities?

We strive to build lasting relationships to produce better health outcomes for all.