This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognizing you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Meeting the Health Care Needs of People Ex

An interview with JSI’s Melkamu Getu,

Regional Health Systems Strengthening Officer for USAID Transform: Primary Health Care Activity

Over the last few years, the internal conflict in Ethiopia has weakened the health system. The emergence of COVID-19 further exasperated the system. The resulting emergencies challenged health system strengthening (HSS) interventions, including those implemented by USAID Transform: Primary Health Care Activity. The Activity partnered closely with the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health for over five years to expand access to higher quality health services for almost 58 million Ethiopians living in six regions of the country, including conflict-affected areas. 1.4 million deaths in children under 5 were prevented, as were more than 85,000 maternal deaths. We spoke with Melkamu Getu, the regional HSS officer, who has been at the forefront of restoration efforts, about JSI’s efforts to manage the conflict and pandemic consequences on the country’s health system.

How much has the conflict affected the region?

A ransacked health facility in Amhara following conflict. Photo: Melkamu Getu

The impact has been severe. Close to 2.4 million individuals have been displaced from their homes and now live in sites with compromised health services and suffer from socioeconomic deprivation. There has been partial or complete destruction of health system infrastructure, looting of medical supplies and equipment, and interruptions to health services—making the community reliant on emergency medical assistance. A 2021 report by the region’s public health emergency operation center noted that 2,343 governmental facilities (40 hospitals, 453 health centers, and 1,850 health posts), 466 private health facilities, and hundreds of ambulances were looted and destroyed in the war-affected areas of the region. As a result of the destruction and looting of health institutions, almost 7million people were without essential clinical and health prevention and promotion services during the conflict period.

In addition, sexual and gender-based violence against civilians, including children and pregnant women have been reported in various war-affected areas of the region. Severe and moderate acute malnutrition is another result of the conflict. During the regional health bureau’s first round of nutritional mass screening, the rate of severe and moderate acute malnutrition in under-5 children was 9.7% (3,479) and 19.4% (6,963), respectively. Similarly, 17,764 pregnant or lactating women have been screened for malnutrition, and 3,966 (22.3%) of them are malnourished. Nearly half (45.1%) of severely malnourished children have yet to be linked to services for treatment due to the absence of supplementary feeding supplies.

The psychological consequences have also been immense, for not only victims but also health providers who display symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, making it a challenge to restore routine health services. In general, years of health system progress in the region have been dismantled.

What major response steps were taken and what was your involvement in them?

During the conflict, the Amhara Public Health Institute and the region’s health bureau conducted rapid assessments and formed an emergency preparedness and response plan. This included regional coordination forums and the establishment of 37 collectives for internally displaced people (IDP). The USAID Transform: Primary Health Care Activity team helped set up the systems for mobile clinics within the collective sites and mobile health and nutrition teams were also deployed. Essential health and nutrition services were provided to IDP sites and nearby health facilities. When the conflict subsided, an assessment of damages on health facilities informed an early recovery plan to reinitiate emergency and essential health services and provision of essential drugs. The government and partners also mobilized start-up kits (essential drugs and medical instruments).

My role was supporting these processes by participating in the regional rapid need assessments; mobile clinic establishment, including availing emergency and essential health services; working on the incident management system coordination forum; and coaching IDP site employees and nearby health facilities (including on checklist and report preparation). I was also involved in the preparation of the region’s early recovery plan and supported health facilities to reinitiate essential health services.

What have been the results of the Activity-supported actions?

Almost all health workers were redeployed to their duty stations and have started to provide services. Gap-filling and sensitization trainings were given to workers at affected sites, which helped them meet the specific needs of their respective facilities. Currently, most of the damaged health facilities have reinitiated their emergency and essential health services.

What has been the most striking experience for you during this process?

During my time working within the IDP sites, I spoke with people who had suffered unimaginable tragedy, including sexual assault and rape, loss of family members, and damage to their homes and livelihoods. Shortages of shelter, food, and essential health care services are adding to the trauma of people who are already going through extreme hardship. These encounters leave a mark and have me in awe of the resiliency of people, who still need a lot more help and will need support for years to overcome what they have endured.

What activities remain?

Although the majority of the affected health facilities have begun to provide some emergency and essential health services, many services have not been reinstated. For instance, immunization, integrated community management of childhood illness, growth monitoring promotion, inpatient care, laboratory services, minor surgeries at health centers, and cesarean sections at primary hospitals are still not available. Therefore, procuring the required medical equipment (which the Activity has already engaged in), laboratory materials, and essential drugs will allow affected health facilities to become fully functional. But I believe the systems we have helped create in response to the calamities have put the public sector in a much better position to fulfil these requirements, as a legacy of the Activity’s support.

What has been your proudest moment

during this process?

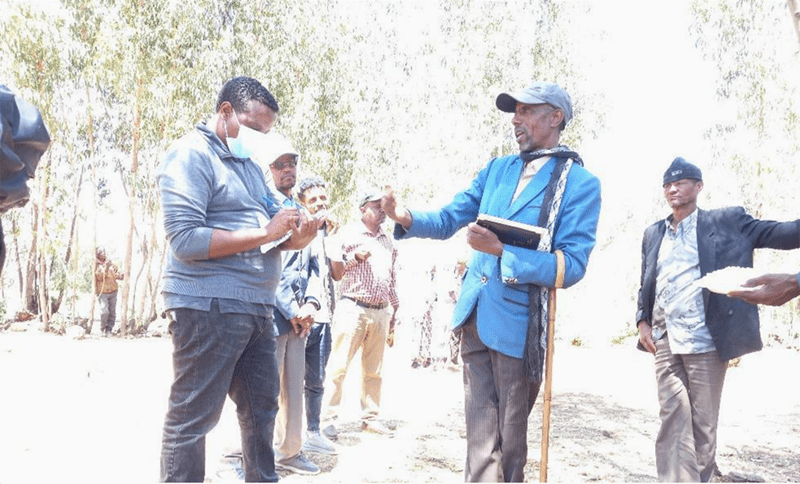

Melkamu (wearing sweater/face mask) supporting assessment of damages and challenges of IDPs.

Photo : Melkamu Getu

It has been a source of pride to save the lives of malnourished children and ease the suffering of people who are going through very difficult times. Along with two colleagues, I have been providing technical assistance for IDP sites in the Waghimra Zone of the region. We worked to reinstate routine health services in facilities; observed the overall status of IDP sites and identified major gaps; and held discussions with the woreda health office and incident command post about these gaps, including establishing mobile clinics within the collective sites. We established a mobile clinic by deploying a health and nutrition team (consisting of five health providers) and providing required drugs and related supplies.

I remember seeing a child in the Tsitsika IDP site where we were providing technical assistance. He was extremely malnourished and fighting for his life. After measuring his mid-upper arm circumference and checking for additional conditions, we admitted him to a stabilization center and ensured it had the resources to treat him. Seeing him slowly recover has been extremely rewarding and is a reminder of the importance of the work we do here, and the lasting impression we have made.

JSI continues to work with the Ministry of Health, community and faith-based organizations, the private sector, and global stakeholders to build strong, equitable health systems that deliver high-quality services to women, children, and adolescents in conflict areas.