Learning from Social Movements: Transforming Systems to Reduce Disparities in Black Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

April 6th, 2023 | story

Maternal morbidity and mortality (MM&M) in the U.S. is a wicked problem, steeped in generations of persistent racial disparities that are now understood to be the symptom of structural racism.

Racism is institutionalized through built-in system structures and processes, perpetuating risk factors that result in disparities, further reinforced through the system’s tendency to maintain the status quo. Entrenchment of racial bias and structural racism (drivers of MM&M) reflect system alignment and stability, perpetuating disparities. In response to contextual changes, the system organically aligns to its point of familiarity—deeply rooted historical policies and structures that perpetuate disparities.

Multi-sector partnerships have a critical role in solving the wicked problem of racial/ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality because they offer the potential to transform systems through healing. These partnerships are a strategy that provide powerful connections and relationships to catalyze significant and lasting systems change. While social movements (e.g., civil rights, Black Lives Matter, Me Too) generated momentum resulting in large-scale system change by disrupting the status quo, efforts to heal systems must follow.

Most public health initiatives focus on solving problems and fixing what is broken quickly. But to paraphrase Rob Ricigliano, that’s not how systems work: they require more than fixing. They need healing—of relationships, historic and ongoing injustices, destructive patterns, and behaviors.

These are problems defined as socially or culturally entrenched and cannot be solved by a single solution, yet the effectiveness of multiple solutions is unknown. A wicked problem is characterized by varying opinions of numerous people who have insufficient or inconsistent knowledge and/or understanding; significant economic burden; and enmeshment in other social and cultural problems (1). These factors, in addition to complexity and long time horizons for intervention outcomes, make wicked problems difficult to solve.

Complex adaptive systems (CASs) rely on feedback to alter their behavior. CASs have permeable boundaries that allow interaction with their environment. They exist within hierarchies of other CASs, and are defined by their relationships between the parts that comprise the whole system, adapting to changes in the environment (context). This continuous interaction creates feedback loops, further driving system behaviors. The power of feedback loops depends upon the degree of connection and relationships, such as those among/within multi-sector partnerships.

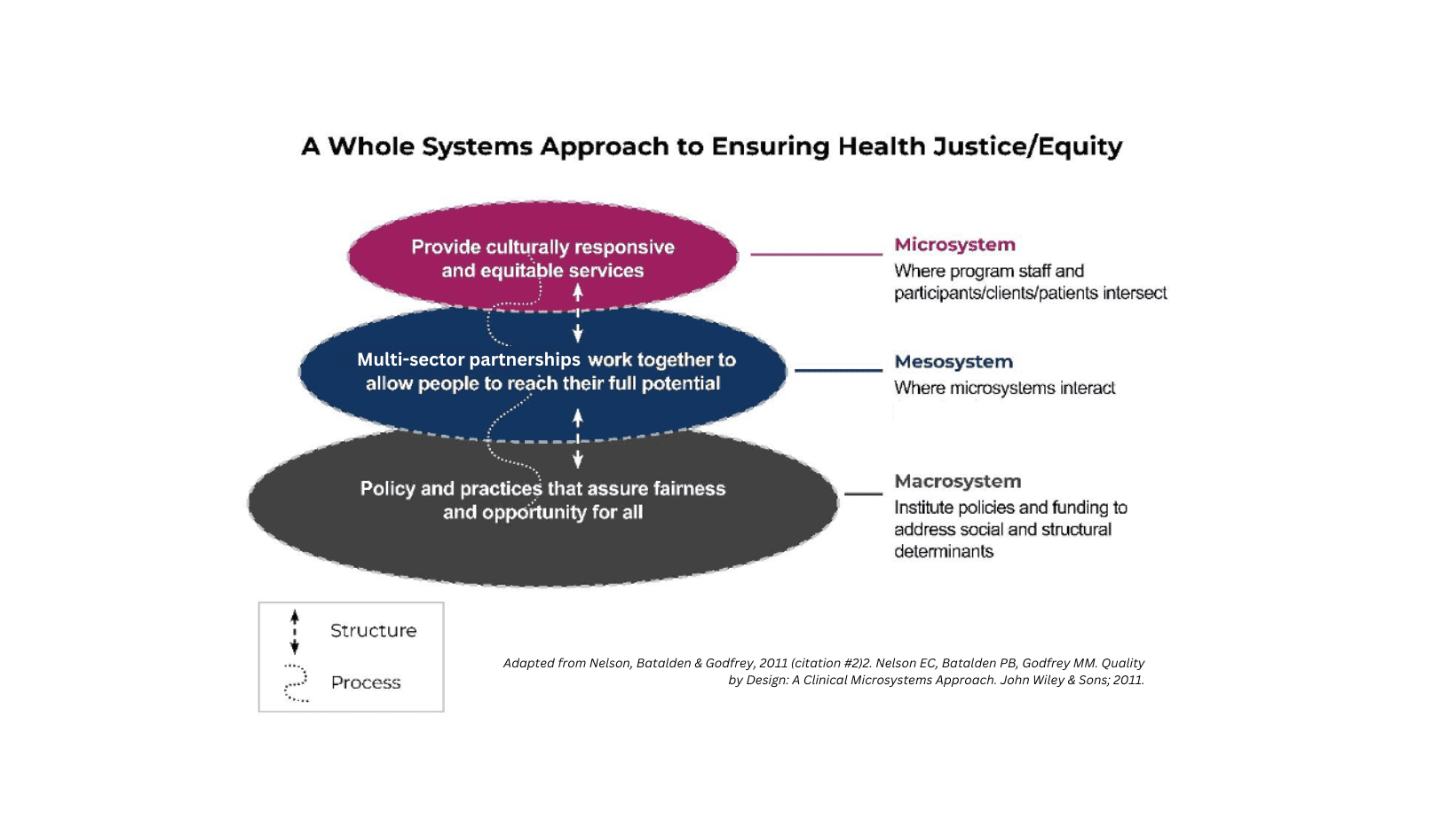

Each level of the CAS relates to the others, and each level has its own function. Multiple microsystems are embedded in a mesosystem, and multiple mesosystems are embedded in a macrosystem. The influence of social movements can be viewed through the following systems’ lens.

The microsystem is the point of intersection between the system of care and individuals. Its function is to provide direct services that ideally are trauma-informed, culturally competent, person-centered and preventive. The civil rights and Black Lives Matter movements shifted hiring practices to promote greater representativeness of the population and meaningful engagement on governing boards. Microsystems are well-positioned to implement small-scale system disruptors (interventions) that test responsiveness to populations and gauge effectiveness of large-order system change through intimate interaction with individuals experiencing the system.

The mesosystem ensures social and structural determinants are addressed within a community by building an effective, responsive system of care, adaptive to changing community needs. At this level, multi-sector partnerships collaborate and implement contextually relevant infant and MM&M prevention strategies. Community partners establish or enhance relationships, communicate their clients’ service needs, collaborate to establish referral pathways, and advocate for reproductive justice. An effective mesosystem depends upon diversity and representativeness of a broad community.

At the macro level, policy decisions affecting social and structural determinants are made (e.g., providing access to safe and affordable housing; high-quality education; reliable public transportation; healthy, affordable food). Governmental agencies and institutions develop and administer policies and resources that affect mesosystem and microsystem functions by establishing funding priorities and performance measures, and regulating adherence to policies. For example, in 2020, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced an urgent, five-year call to action to improve maternal health. Supported by HRSA funding, it develops community-level action plans to reduce infant and maternal mortality through “upstream” interventions and multi-sector community partnerships (3).

Current system behavior is influenced by past activities or actions. The system, as currently aligned, reinforces and perpetuates wicked problems such as gaping racial/ethnic disparities in MM&M. The work is not about merely aligning systems, it is re-aligning them for healing. Wicked problems require collective (reinforcing) action at each system level. Public health can cultivate a transformative movement that releases the power of multi-sector partnerships to overcome racial disparities in MM&M and other wicked problems. This calls for whole system goals that promote racial and health equity (4, 5).

Learn more about this framework in the Community Health Equity Research and Policy journal summer 2023 edition.

Authored by Naomi Clemmons and Lea Ayers Lafave

We strive to build lasting relationships to produce better health outcomes for all.